What are the main differences between Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease and someone who has typical, Late Onset Parkinson’s disease? Why does this subclass of disease exist in younger people, relative to typical Parkinson’s in more elderly people?

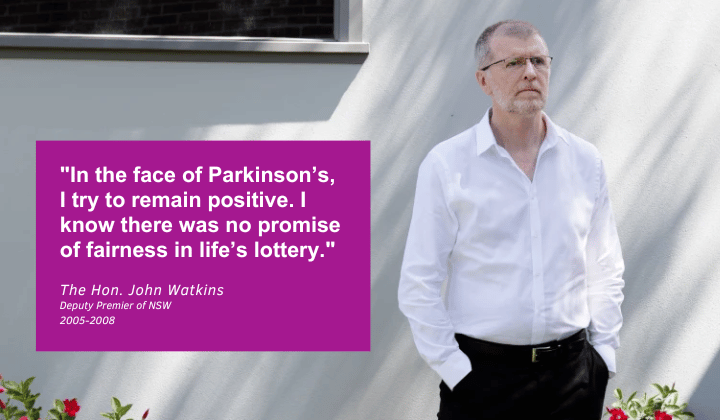

Author and healthcare writer Mark Chlad – who is himself living with Young Onset Parkinson’s – takes us through some of the everyday issues and choices that people in his situation may have to face.

How many people with Parkinson’s have the Young Onset form?

The estimates vary widely because organisations use different age brackets when discussing how many Young Onset patients with Parkinson’s exist at a given point in time. However, most organisations appear to be moving towards the age of 50 years as the point at which patients with typical Parkinson’s develop symptoms.

In 2018 the number of people living with Parkinson’s in Australia was around 82,000, making it the most common major movement disorder1. By 2022 estimates had risen to somewhere between 84,000 and 212,0002 in Australia. In the USA, Young Onset Parkinson’s occurs in 4 to 20 percent of all patients with Parkinson’s.

While symptoms are similar to typical Late Onset Parkinson’s, people with the Young Onset form have different challenges to face. Because they are at a different life-stage, challenges in employment and finance may occur. If these issues cannot be resolved, the person with Young Onset Parkinson’s may experience challenges in the family setting and in personal relationships.

What were the main challenges with employment and creating regular income?

The biggest challenge I faced when I came to Australia in 2010 was finding work relevant to my experience along with an employer who could see the potential in me (plus the experience and knowledge I could bring to a company).

I deduced that getting a new job was all down to the interview process, which for me usually presented the following scenarios:

- I could begin the interview with a ‘cards on the table’ approach: “Now, some of you are looking at me, thinking ‘what’s wrong with this fella?’ Well, it’s called Parkinson’s.” Notebooks all closed in unison and the interviewing panel studied my responses to questions fired at me over the course of the interview, as if I were a new specimen they were viewing under a microscope…NO second interview!

Or…

- I could begin the interview with a ‘cards close to the chest’ approach: I would say nothing about my Parkinson’s and just hoped that the doubled-up dose of medication I took beforehand would continue to work through the interview – without dyskinesia! Usually this would end up with a frustrated interviewer who could see something was ‘not quite right’ about this candidate… NO second interview!

Both approaches are poles apart in strategy and were both as ineffective as the other. It is very frustrating with respect to the 400 jobs I applied for and the handful of interviews that I was offered in the first few years of living in Australia.

Differences between Young Onset and Late Onset Parkinson’s?

One of the main differences is the rate of disease progression, which is slow in people with Young Onset Parkinson’s, maintaining functionality and remaining cognitively unimpaired for a longer period of time. This may explain why people with Young Onset Parkinson’s tend to live longer than people with Late Onset Parkinson’s.

As I was going through my own diagnosis, my specialist told me that my rate of disease progression was in the top half of a percentage point. What he was trying to say was that my condition was the slowest progressing for every 200 of his patients.

People with Young Onset Parkinson’s may demonstrate an increase in side-effects, particularly more frequent dyskinesias or involuntary body movements from dopaminergic medications. Earlier and more frequent dystonias (cramping, unusual posture, arching of the foot) are common in Young Onset Parkinson’s.

Lastly, people with Young Onset Parkinson’s are less likely to develop dementia.

Why is it important to differentiate Young Onset from Late Onset Parkinson’s?

Recent research in Parkinson’s has identified a way of telling if a person is likely to get the disease. The implications of this test, known as the alpha-synuclein assay, for both Young and Late Onset are enormous. The possibility of living in a world without Parkinson’s has never looked more certain. But how will it affect both people with Young Onset and people with Late Onset Parkinson’s?

The alpha-synuclein assay could pave the way to developing medicines that stop the higher rate of disease progression from increasing further in people with Late Onset Parkinson’s. Then, existing or new medicines can be used to minimise the stabilised symptoms. This would be a major breakthrough in the management of Parkinson’s.

In Young Onset Parkinson’s there are two main scenarios. The first is treating the Young Onset patient who has presented with two or three mild symptoms. As with the Late Onset patient before, using medicine that stops the disease progression to allow doctors to evaluate and treat stabilised symptoms may be possible.

The second scenario – and one of the most exciting things about the alpha-synuclein assay – is that the test can tell if someone has Young Onset Parkinson’s but has no symptoms. This means that the development of medications that block the development of Young Onset Parkinson’s – before symptoms develop in at-risk patients – is a clear possibility.

But the best part is yet to come. By taking a blood sample or a more preferable, less invasive nasal swab sample from a child (perhaps 2 or 3 years of age) it may be possible to identify people who are at risk of developing Young Onset Parkinson’s. Not only that, but it should also be possible to identify who is at a higher risk, allowing treatment prioritisation to occur.

A vaccine for Parkinson’s disease may not be as far away as we think!

Mark Chlad is a healthcare writer. He has written and had published two books about his adventures with Parkinson’s Disease, ‘Drivin’ Daughters and Parkinson’s’ and ‘The Time Thief’ (both under the pen name: Marco Preshevski). These are available online via retail book shops’ websites or can be ordered through any bookshop. Marco’s third book is due out in 2024.

References