Parkinson’s and depression

Gut health and development of Parkinson’s

2nd April 2021

Parkinson’s nurses in action – Tony and Jenny

3rd April 2021Parkinson’s and depression

Parkinson’s and depression

By Dr Nichola Davies

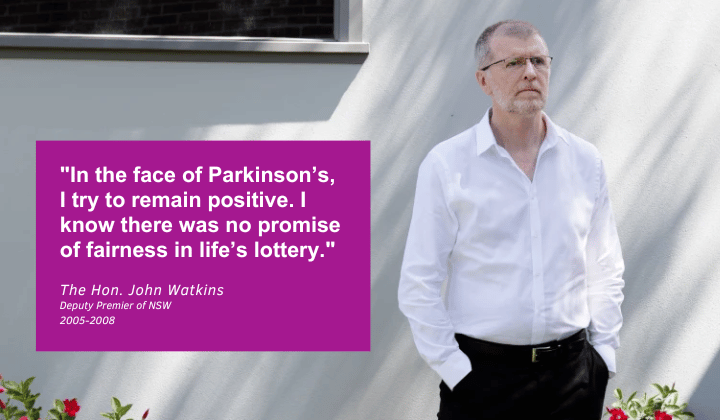

It’s well-documented that people who have been diagnosed with a chronic illness such as Parkinson’s are at higher risk of developing depression as well.

Indeed, it’s estimated that 50 percent of people diagnosed with Parkinson’s will experience depression.

The following scenario is a common experience among many newly diagnosed Parkinson’s sufferers.

First there is confusion: ‘What does this mean?’, ‘What can I do?’, ‘How will this impact me?’

Then the shock comes as the reality of the disease sets in and the impact that it will have on the rest of your life is realised. The shock gives way to grief and depression.

The feeling that your life has ended, and your hopes and aspirations have been shattered is less time than it takes to make a cup of tea.

As one person with Parkinson’s told us, “When I was diagnosed, I came home and cried. I thought it was the end of my life.”

However, receiving a diagnosis for Parkinson’s isn’t the only factor that can cause depression in people with this condition – the very course of the disease changes the brain chemistry that usually keeps depression at bay.

Experiencing depression after receiving a diagnosis of Parkinson’s isn’t a sign of emotional weakness or a flaw in character. Depression is caused by an imbalance of chemicals in the brain, which is what Parkinson’s is all about: low levels of chemicals in the brain.

There is evidence that suggests depression is an early symptom of Parkinson’s. Despite this, people with Parkinson’s aren’t routinely tested for depression and therefore might not receive treatment for the condition.

It remains unclear whether the medications prescribed to reduce the physical symptoms of Parkinson’s contribute or worsen symptoms of depression. It is also unclear how Parkinson’s affects pre-existing depression or how medication prescribed for Parkinson’s impacts pre-existing depression.

Depression is treatable even if it co-exists with other conditions. Depression is also limited in duration.

Often, finding the right mixture and combination of drug therapy can improve both the physical symptoms of Parkinson’s and the symptoms of depression. However, it is important to know that the treatment of Parkinson’s must be comprehensive and include both the physical as well as the emotional symptoms.

Reaching out can also ease the depressive symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease. As one patient told us, “I started meeting other people with Parkinson’s and it helped all of us to talk to someone who had the same condition.”

There are many physical and online communities where other people with Parkinson’s can meet up virtually, or in person, and share their experiences with others who are feeling the same and suffering from similar symptoms.

Most importantly, you have to set a goal in for your life. Unless you have something to aim for, or something that drives you to get up every morning and face the day fighting, you will find yourself drifting through life.

It is best to accept that you have Parkinson’s and move on.

Dr Nicola Davies holds a Master’s and a PhD in Health Psychology. She is a member of the British Psychological Society and the Division of Health Psychology.

Source

First published in Parkinson’s Life